Review: 4 stars

My mind cannot comprehend war. I have of course seen the movies and the documentaries, read the books by all the right authors – yet, fail to comprehend the immensity, brutality & the utter meaninglessness of war. I let myself be mindlessly pumped-up by jingoist fervor over a primetime debate on television, or bay for blood over social media news-feed.

It’s not a question of right and wrong. Kurt Vonnegut in Slaughterhouse Five tells me that there are no villains in wars, or for that matter, heroes. Nobody is morally right when they wage a war, and the victors do not have God on their side. Well, that’s my interpretation of the book – and that comes from the guy who grew up adoring Mahabharata, as literally the greatest epic ever told – and it did feature a God on victor’s side! So of course, this book doesn’t sit well on my psyche, it has ruffled a few metaphorical feathers over my lanky frame and I find myself to be circumspect.

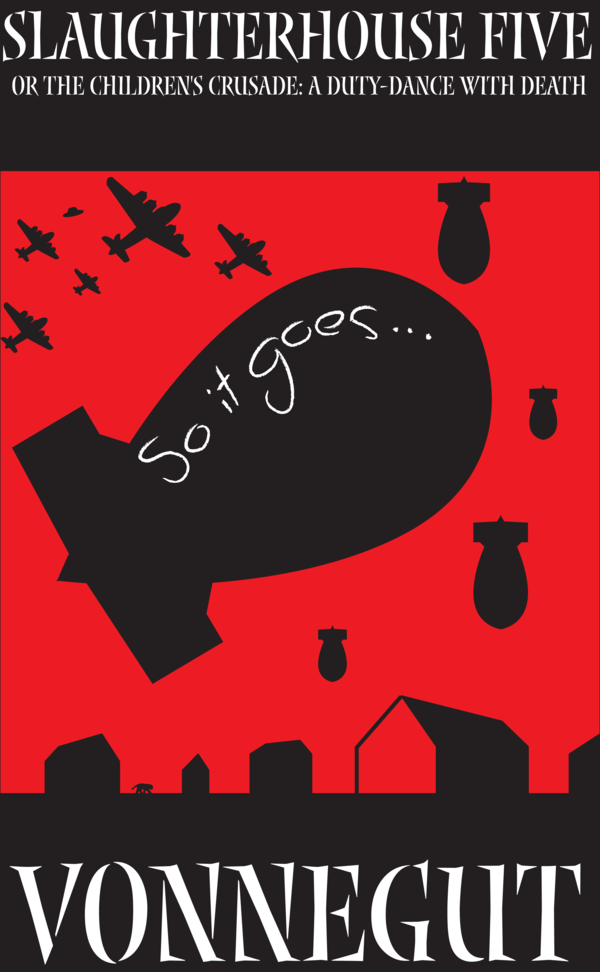

Slaughterhouse Five is the story of Billy Pilgrim and his horrific experiences as an American prisoner-of-war who had witnessed the bombing of Dresden, Germany by American and British warplanes in World War 2. It is also a story of his coming to terms with war (or his utter inability to do so) by believing that he has come unhinged in time – that he can travel into the past and the future, by believing that he had been abducted by an alien species called the ‘Tralfamadorians’, by believing that he could see whole of the time as is, the past-present-future with no cause & effect, complete and inexorable, by believing that free will is a myth and that he did what he did because he had no choice. And thus he let go of the guilt.

Really, there are no ‘characters’ in this tale, unless you count the high school teacher Edgar Derby who feebly stood up for all things American, and was later shot by the firing squad for stealing a teapot. According to the protagonist, in addition to there being no characters in the tale, there is “almost no dramatic confrontations, because most of the people in it are so sick and so much the listless playthings of enormous forces….” No one has redeeming qualities, everyone is brutal and everything is grim. Behind the enemy lines you find one American socking the other, and when the Germans pounce upon them, the one who is beaten thinks them to be beautiful god-sent angels with whom he instantly fell in love.

The withering writing spares nothing and no one – not the Americans, not the Germans, not free-market capitalism, not the Russians, not the Bible, not Communism, not Nazism. Everyone is to blame. There is no black and white – war renders everything grey. This is not so much an un-American book as it is an anti-war book. Ironical though, that the book proclaims that you could do nothing to stop the war. I guess the author wishes to shock the reader with its unsentimental, apathetic and nihilist tone.

The form of the writing is unique. The story doesn’t proceed in the usual fashion of Exposition – Rising action – Climax – Resolution. Because the Tralfamadorians and Billy Pilgrim can look at all of the time together – the story jumps across past, present and future, to try to give us a complete picture. And even if we do not believe in the existence of Tralfamadorians or the non-linearity of time, our memories and the way we recollect them are non-linear. The aliens and the time-travel are the constructs to help Billy Pilgrim come to terms with his horrific memories of the war. And there are markers which connects his memories. A marker in the form of ‘radium dial’ connects his childhood memory of exploring a dark cave with his family as he remembers that his father wore a watch with radium dial, to that of his war-time memory when he describes the starving Russians as having the faces like radium dials. If you look carefully, there are many such markers sprinkled in the text (‘Three musketeers’, ‘Children’s crusade’ etc.) which connects different memories and that is exactly how we recollect and cope with past. Therefore the form of the writing isn’t chaotic, it’s more natural.

I can’t say whether this book has affected me or not. But it surely has an effect of a pebble in calm waters, it has disturbed me. Its wry humor in the face of awesome tragedy, its unsparing nature, its distanced prose and its utter lack of empathy – has indeed shocked me into introspection of my own feelings regarding war.

It’s implicit that death shouldn’t be taken lightly. So it goes.