Review: 3 stars

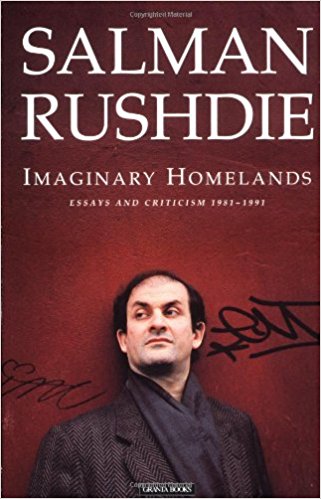

Salman Rushdie is a notorious name-dropper, or I must be simply unaware about the major chunk of literature that he enjoys and sometimes reveres. If this is the popular culture out there, then I must be the ostrich with my head in the ground. Or I can always say that it is the late 80s he’s talking about – a period in which I wasn’t even born, my libraries aren’t build around the books of authors he critiques in the pages of Imaginary Homelands .

But of course, Imaginary Homelands has much more to do with people, politics, religion and popular culture, trying to paint an understanding of the conflict between ideas of orthodox stasis and malleable flexibility of all that is modern and secular, the anguish of being uprooted from the homelands across time and geography, of wanting to hold to the past and wanting to embrace the future. Imaginary Homeland is a personal quest of an immigrant caught in the crossfire of Western cynicism and Eastern intractability, being shaped by the conflicting narratives of both while making a brave attempt to shape them, in turn. A finance guy looks at the world through numbers, Salman Rushdie thinks everyone to be an immigrant caught in a struggle between control and release. In these pages, according to my humble opinion, he tries to fit the world to his hypothesis.

And just like Salman Rushdie actively encourages his readers to do in one of the essays, I will not hold the book and its central theme to be absolute truth (while considering the medium/the channel/the stage to be sacrosanct). While I understand and feel for his predicament (after the issuance of fatwa for Satanic Verses ), I fail in my attempt to empathize – because I couldn’t think of a similar experience in my own sundry life. While his vantage point as an immigrant does have certain distinct advantages – he is bang-on about the rise of a Hindu narrative of India, censorship and maybe about the apathetic, passive racism in the West (being in India all my life, I wouldn’t have experienced it); but I feel that he embraces more of West, and rejects more of East with each passing page. He rejects the tag of being a “commonwealth” author – and it gets my goat not because he is resisting some imperial, old-empire prejudice, but for his keen desire to belong to the West and its literary culture. While he eagerly talks about the politics of his old, imaginary homelands of India and Pakistan and maybe rightly criticizes them, the ideals and inspirations and aspirations that he holds dear as an author and a human being are largely western. It might be argued that the authors whose books he critiques in these pages are from around the world, but they are “West-approved” discoveries which he talks about in a gleeful, dervish-delight.

He calls himself an immigrant, nurtured in the cauldron of mishmash cultures. I do not mind him criticizing India and its culture and its politics, but that he does that in that snobbish accent of his – infuriates me.